|

|

The

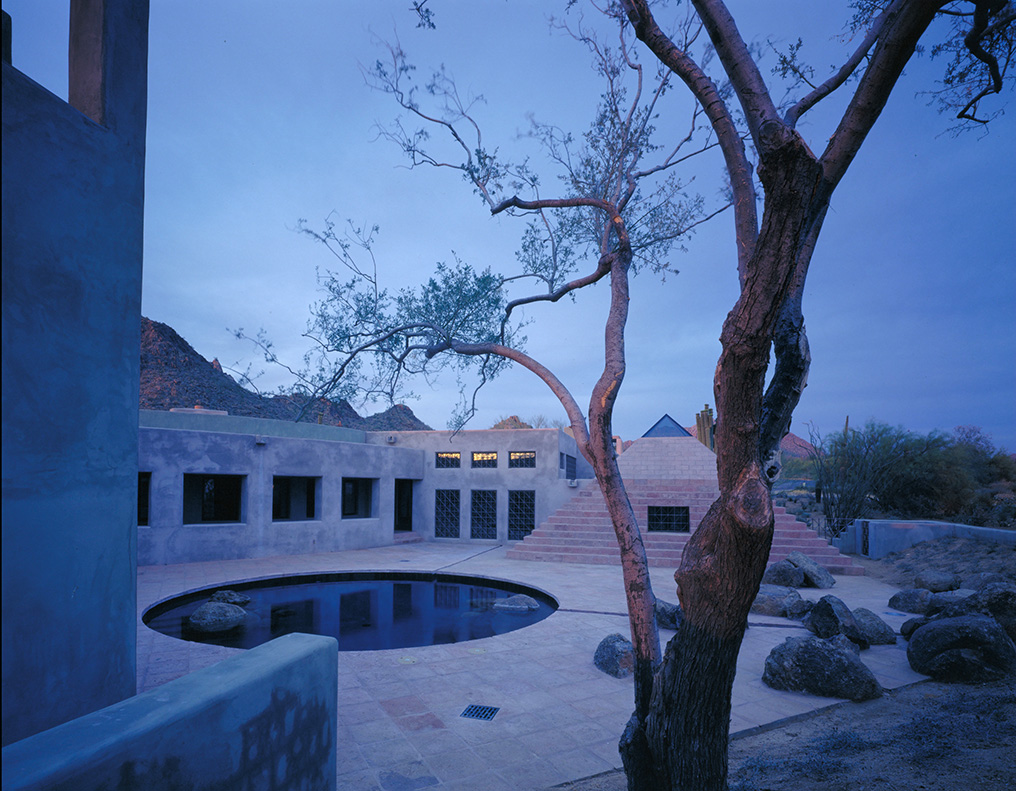

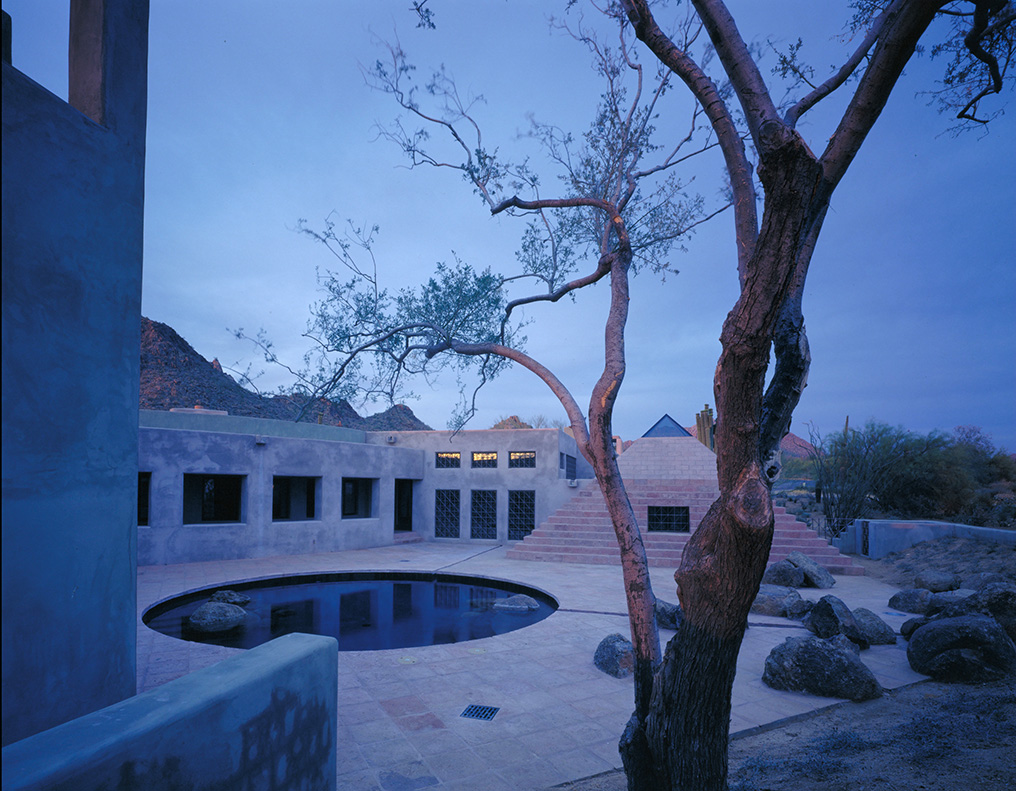

White House Scottsdale, Arizona 1986

This High Sonoran desert site is enclosed by peaks and eroded granite ridges. Below this encircling rim, sparse vegetation, at once hardy and fragile, surrounds the house and speaks of the adaptations necessary for life beneath an unremitting sun. In this desert environment, architecture, landscape and human procession join in a synchronous dance. The low, weighty perimeter of the house connects in its massiveness and its color to the powerful geologic context. Contrasting brittle steel shade structures create shadow patterns that recall the tracery cast on the site by the lacy branches of the Ocotillo and Palo Verde. The house is axially positioned in relation to the east-west travel of the sun. Daily living patterns shift from morning to evening. A sunrise-viewing pavilion is situated above the breakfast room; an interior ‘canyon,’ a gallery with centered, sequential water system, leads past kitchen and dining fragments as the ‘mountain,’ the pyramidal study, introduces the ‘valley,’ the central courtyard; across the ‘valley’ a trellised, sunset tower completes the sequence. Inside, water issues from a black granite block and runs through a channel parallel to the east-west axis of the house. The water’s path culminates in a quiet pool in the courtyard. The gentle standoff between built form and a desert environment is expressed in the project as a poetic tension. The line of demarcation between the house and the terrain becomes ambiguous. At certain places the desert enters as a boulders tumble into the courtyard. Refuge in this arid precinct has been created by the presence of water, shade and enclosure. Looking out from this sequestered desert retreat, the majestic landscape and the vast sky become theater. A significant part of the house is set partially underground providing thermal stability while capturing eye-level views of the desert landscape. The higher vantage points, like the sunset tower, have views across the valley toward nighttime lights of Phoenix, to the sunset in the west, and to the mountains in the east. “Sparse, astringent, vast and gritty, a desert environment poses special problems for an architect who wants to build in it. To ward off the ferocious, unremitting sun and heat-drunk earth, he may build a fortress, all blind walls and stony parapets, as if to defy the hostile elements. Or again he may shrink his building into its surroundings, half-burying it in the ground, like the desert wildlife, which hides in holes by day and comes out to prowl only at night. A special condition of desert building is that neither strong nor weak points can be softened by the application of cosmetic shrubbery. Indigenous plants are spiky and scattered; imported vegetation needs constant water and produces an instant, artificial California. Like the bones of the landscape, the building must stand forth in its own structural right—but not too much. Thus the architect balances on a knife-edge between building too forcefully (against his surroundings) and building too self-effacingly (so that his work disappears into the surroundings). The house built on the out-skirts of Phoenix, Arizona, for Gene and Donna Fuller by Antoine Predock not only treads that knife-edge, it transforms the balancing act into a deliberate, graceful dance.” -GA Houses, December 1986

|

|

|

||

|

|